Like many of you, I haven’t been in a museum since the pandemic closed them all in March. A few weeks ago, though, I returned to one of my favorite places in Cologne, Museum Ludwig, to explore their new exhibition: Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: Original and Fake. Questions, Research, Explanations.

I looked at the years-long process that went on behind the scenes to determine the authenticity of 49 works in their collection in my first story for The Art Newspaper. Here’s an excerpt:

Suspicious works of art are normally consigned to a museum’s storerooms. And it is likely that the Museum Ludwig will send its falsely attributed works to the depot once the show ends in January. But in going public with its authentication research, the museum has made a clear commitment to preserving accuracy in a field flooded with fakes.

…

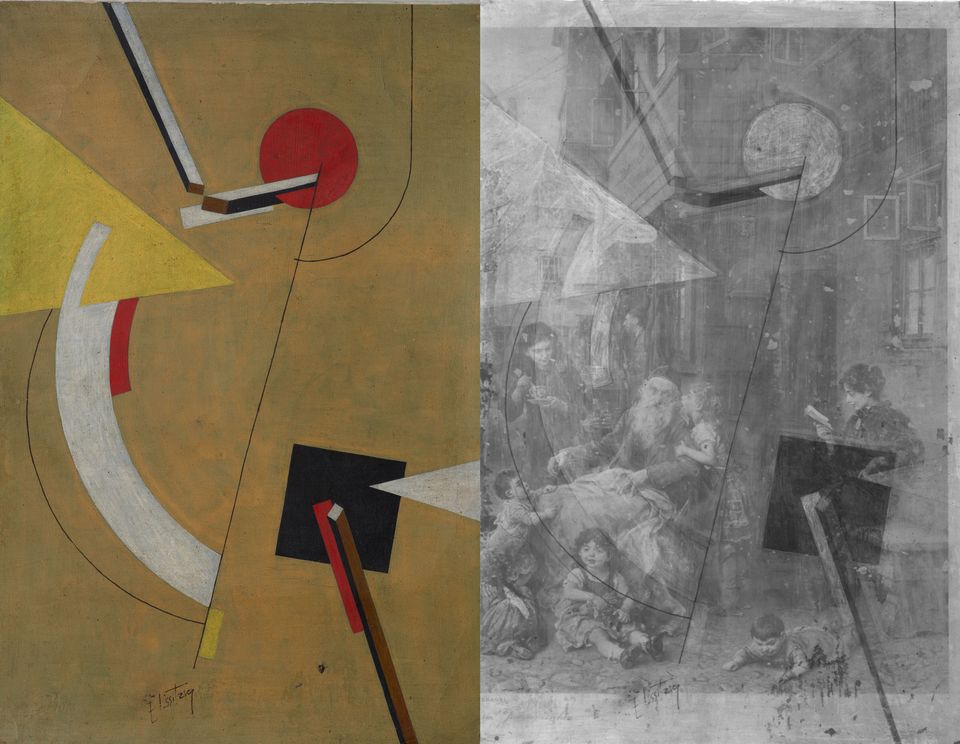

A team led by Jilleen Nadolny from Art Analysis & Research Institute, a private London firm, studied the works with technologies including 3D surface scanning. “By looking with the microscope, combined with X-ray and infrared imaging, which allows us to see below the surface, we could confirm how the artists worked,” Nadolny says. “These might look like wild, spontaneous brushstrokes. You don’t see any underdrawings, yet they are there, guiding the artist’s hand.”

“Having a baseline technical analysis like this can help detect forgeries later,” she adds. “It’s a great benefit to understanding an artist’s work, and to protecting their legacy.”